Pertaining to the Stars

“We have calcium in our bones, iron in our veins, carbon in our souls, and nitrogen in our brains. Ninety-three percent stardust, with souls made of flames, we are all just stars with people names"

Prologue

It’s a long way from home to the upper slopes of Mauna Kea, Hawaii. I remember that first night. As we drove up the Mauna Kea access road to 9,000 foot elevation the air pressure began to drop, breath shortening. The breeze felt dry and crisp, and the earth would crackle on every pebble as we walked. We rolled out a number of small telescopes onto the stargazing patio. I had seen stars before but not in these numbers. It was like being engulfed in an ocean of phosphorescent lights.

It was there that I could see the very workings of the universe in full bloom - the constancy of the Sun and Moon and our ancient history in the stars. And within me lived the innate desire, shared by humanity in all ages, to learn the story of our origin by understanding the cosmos

Connecting With the Light

We arrived here, predestined to observe our place in the cosmos from the mineral -rich and watery planet we call home. In modern times, this destiny has taken us into the far reaches of space, searching for answers. Like a newborn baby peeling open its little eyes onto the world for the first time, we looked up to see, to know, who and what we are. As we gaze at the night sky, our celestial mother, we become absorbed by the effervescent full moon outshining the assembly of stars. Or maybe something subtler calls - the faint and innumerable distant suns. Carl Sagan famously said, there are more stars in the universe than all the grains of sand on earth.

How deeply we can directly perceive our known universe with two feet on the ground ends with the limitations of our sense of sight. Classic Indian Astrology, Jyotiṣa, is known as “the eye of the Vedas.” Its foundations rests on the many subtleties of pratyakṣa, direct observation, the central theme of the first issue of this journal. As our lens onto the cosmos, pratyakṣa connects us to the lights from which we came. They dazzle, enchant and guide us towards understanding who we truly are. Ancient sky watchers were not as limited as one might think in understanding our place in the universe from where we are here and now, our Earth.

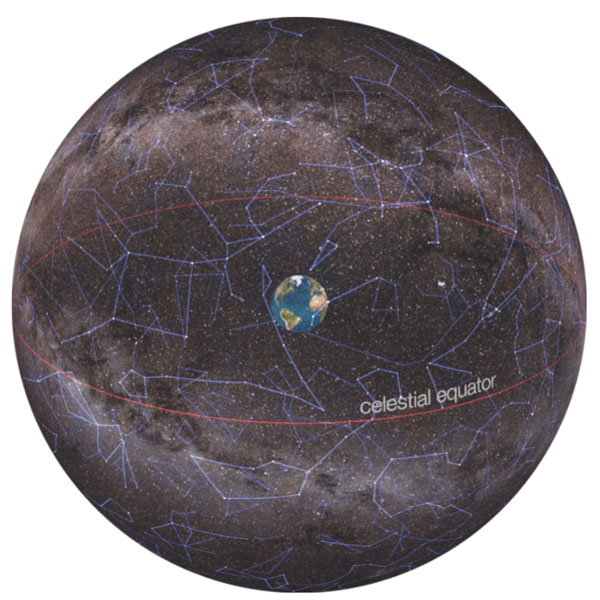

In the absence of the Sun’s rays, nightfall reveals to us a canopy of shimmering stars. The furthest we can see in all directions with our naked eye is known as the celestial sphere. The ‘fixed’ nature of these stars is but a reflection of their great age and distance. Their lifespan is far beyond our limited experience and the light we see traveled an unimaginable distance across the universe to reach us. In that way they have a seeming permanence and are the oldest visible linkto our origins and ancestors.

The Three Spheres

The Vedic tradition calls this brilliant circle of stars bhā gola (the shining sphere) based on the Sanskrit derivation of bhā meaning to shine, inspire and illumine. It’s not hard to imagine thinking of these outer-reaches of the sky as the highest heavens. Bhā represents the map of fixed stars and is the outermost of three spheres.

The Earth, the realm of man, is the innermost sphere or bhū gola. It is suspended in space in the center of the celestial sphere which is like a giant globe. The space between Earth and the shining heavens is kha gola, empty space, air, ether or sky. It is in kha gola that we see the orbiting bodies, the solar system moving against the backdrop of the fixed stars of the celestial sphere. The classical Indian tradition invokes this concept of three spheres or golas not only in describing the cosmos but by frequently invoking alignment to these three worlds - earth, sky and heavens - as a powerful component of their worship.

The Cosmic Highway

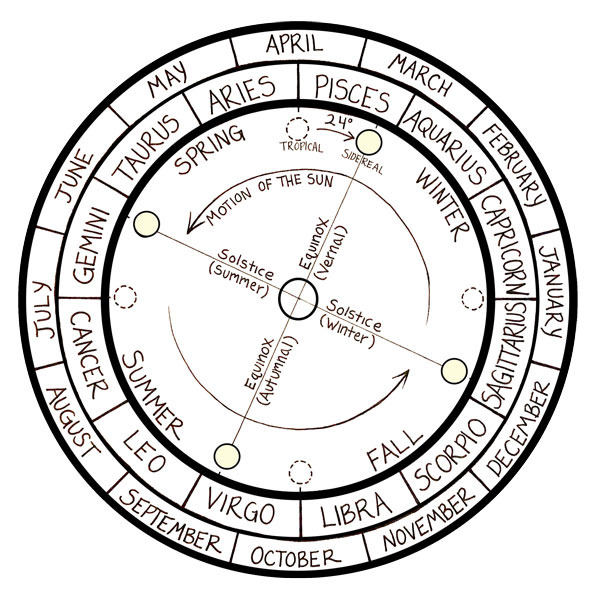

Ancient astrologers were also well aware of the heliocentric nature of the solar system with the Sun in the center, and yet, we perceive the cosmos as an observer from Earth. Hence, for the purposes of astrology, we take a geocentric view of the heavens. For example, if the Moon is in Taurus, this means that for an Earth-based observer, the Moon appears against the backdrop of the stars known as Taurus. So the location, Taurus in this case, is relative to the observer.

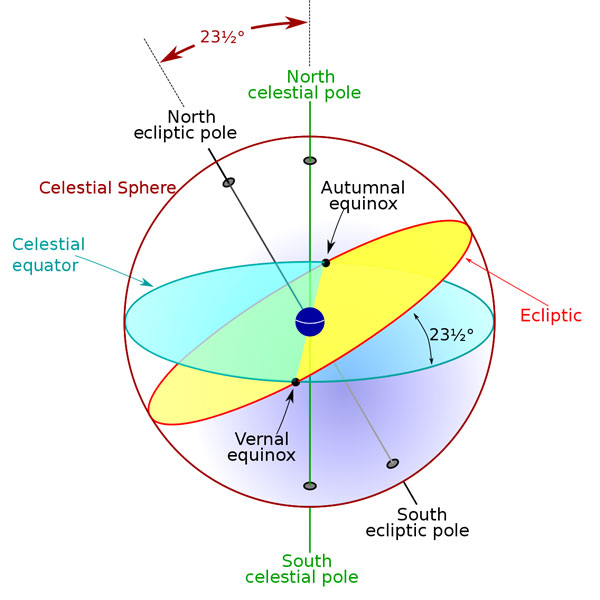

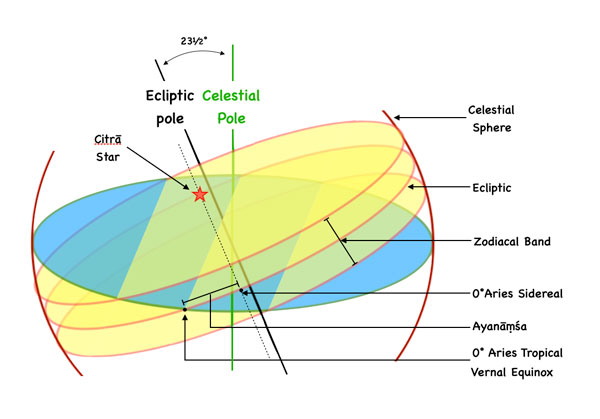

There are two circles that define the arrangement of the solar system and the Earth’s position in it. The first is the celestial equator, the projection of the Earth’s midpoint from the north and south poles to the outer reaches of the celestial sphere. The second is the all-important royal path of the Sun, the ecliptic. As the Earth completes its yearly cycle around the Sun, we observe it in reverse. From earth, it appears the Sun traces a path around the fixed stars. This is the ecliptic referred to in Sanskrit texts as the Sūrya Marga, path of the Sun and the cosmic highway along which the grahas travel.

Due to the tilt of the earth on its axis, the earth rotates at about 23° angle to the plane of the solar system. This causes the Sun’s path to intersect with the celestial equator at the seasonal marker points of the Vernal (spring) and Autumnal Equinoxes. The equinoxes are vital to understanding the seasons and a reference point by which planets can be located.

From earth it appears that all the grahas rise in the east and set in the west; this is due to the one full counterclockwise rotation of the earth on its axis every 24 hours. The ‘proper’ motion of the grahas through the fixed stars is from west to east.

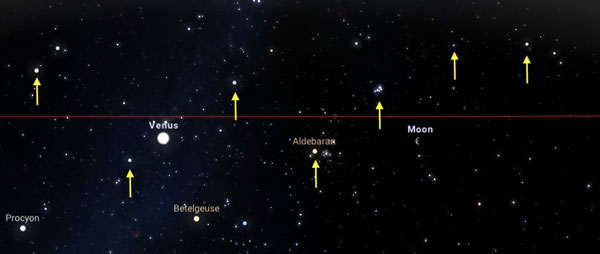

The image below shows the cosmic highway. It is approximately 16° degrees wide with the Sun’s track, the Sūrya Marga, at the center and the rest of the grahas wandering within 8° north and south of the ecliptic. The Sun is tracing the line of the ecliptic in red with the planets traveling westward a little above and below the Sūrya Marga.

When observing the night sky, planets look like moving stars. The Greeks called them planets which means ‘wanderer’. In Hawaiian star-lore, they are called Hoku’aea, which quite literally means moving star, Hoku ‘star’ and ‘aea’ moving. Indian astrologers use the word graha which means to seize or grasp. Since planets have no light of their own, they can only ‘grasp’ that which can be reflected by the sun, the star of our solar system.

The Nava Grahas

The nine grahas in Classical Indian astrology are called in Sanskrit the nava grahas. This includes the seven celestial bodies visible to the naked eye - the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, as well as Rāhu (the north node of the Moon) and Ketu (the South node). Since Rāhu and Ketu are mathematical points rather than physical bodies, they have no form or light. In Jyotiṣa, Rāhu and Ketu are called chāyā grahas (shadow planets) as their alignment with the Sun, Moon and Earth at certain times creates shadows which block the visibility of the luminaries. This creates the visual phenomenon of eclipses.

Although planet means wandering, their movement is far from random. Understanding and harmonizing with cycles in nature was vital to survival so the natural impulse to understand and order what was observed led to mapping of the sky, predicting patterns, and then codifying the cyclical movements of celestial bodies. Originally, astronomy and astrology were a unified system of knowledge based on observation and calculation. In ancient India, the position of the grahas was determined by observing them against the visual backdrop of the fixed stars of bhā gola.

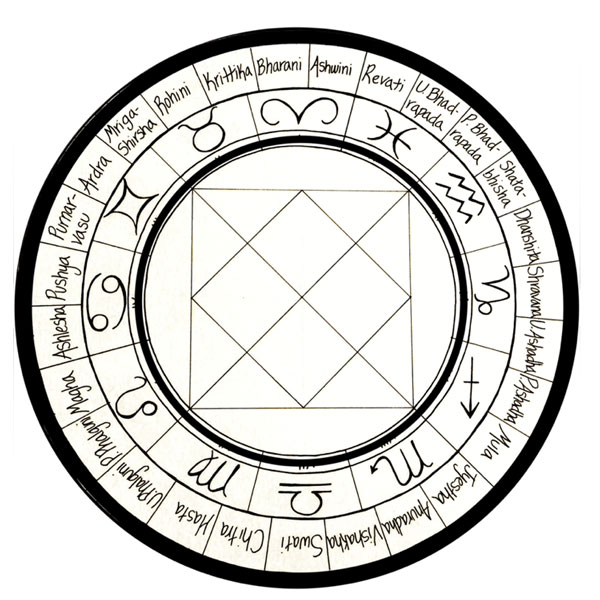

The Twenty-Seven Sisters

Since the Moon is the most visible of the grahas, it is easy to track on its journey around the ecliptic. It is therefore not surprising that the Indian tradition is originally based on the movement of the Moon through twenty-seven distinct lunar “mansions” referred to as the nakṣatras, thus dividing the great ecliptic circle into twenty-seven smaller groupings of stars (asterisms).

It is said in the tradition that the Moon married twenty-seven sisters and was charged by their father to spend one night in the mansion of each one. It is a charming and memorable way to mark the Moon’s journey through the circle of stars. The nakṣatras are imbued with meanings from the patterning of the stars themselves, their Sanskrit names and derivations and the wealth of stories associated with the deities ruling each one of them. As an oral tradition, these stories were passed down from generation to generation often containing astronomical truths symbolized by the stories.

The “mansions” are spaced to accommodate the Moon’s swift average daily speed of 13°20’ (27 x 13°20’ = 360°). Bright stars that dot the ecliptic beckon the Moon to the right “address”. These marker stars are known as yoga tārās, the ‘chief stars’ of the lunar asterisms marking 13°20’ zones of the ecliptic. days, I still love to follow the waxing Moon as it leaps from one yoga tārā to the next night after night. The first photo in this article is the nakṣatra of Kṛttikā (the Pleiades), one of the most beautiful of the brightly lit star clusters around the ecliptic. All the grahas wander with the Moon through this band of stars around the ecliptic. The lunar asterisms provide a more precise zone for locating the position of the grahas.

The Two Zodiacs

Jyotiṣa uses the Sidereal Zodiac, translated as pertaining to the stars, to locate the grahas along the ecliptic for predictive purposes. Another way of dividing the circle of stars is into twelve 30° spans, the more familiar Tropical Zodiac used primarily in Western Astrology. It is based on the solar cycle. Twelve larger groupings of stars configure with the monthly movement of the Sun. These are the constellations of Aries, Taurus, Gemini etc. The convention is that the twelve solar constellations are 30° each giving the 360° circle of the zodiac. Though not every constellation fits neatly into a 30° span, it is close enough for the system to be a reliable mirror of the night sky.

The ecliptic is the common thread whether you follow the grahas moving through the Moon’s mansions or through the twelve zodiacal constellations. Therefore the nakṣatras inhabit that same circle of stars. At some point, the rāśis (solar constellations) and nakṣatras were integrated in Jyotiṣa and the reference point of 0° Aries established where a graha would be located along the ecliptic.

Though locating a graha along the ecliptic is the principle measurement used in chart analysis, the two main systems of astrology use different reference points.

The Shining Jewel

Let’s explore that difference between the Tropical and Sidereal zodiacs. To start, The Tropical Zodiac determines 0° Aries from the position of the Sun at the Vernal equinox, irrespective of the constellation it is residing in. Whereas the Sidereal Zodiac uses the Sun’s visual position as it passes over 0° Aries, an unremarkable patch of the zodiac devoid of a marker star. However, the brilliant light of the fixed star Citrā (Spica), sitting at 0° Libra, points directly across 180° of zodiacal arc and marks the sweet spot of 0° Aries. Even if there were stars at 0° Aries, you couldn’t see them if the Sun was there. Citra is perfectly positioned as it would be visible setting in the West right as the Sun rises in the East at 0° Aries.

As the earth rotates on its axis year after year, it wobbles ever so slowly, like a slowly spinning top, causing the two points on the ecliptic that we attribute to the vernal and autumnal equinoxes to inch themselves westward, opposite to the proper motion of the plane. This phenomena is called the precession of the equinox - a slowly widening gap between Sidereal 0° Aries and the vernal equinox which is equated with 0° Aries in the tropical system.

Another way to think about is is that the Sun, as it is crosses the celestial equator on its northerly track, does not quite make it back to the same ecliptical longitude the next year. It misses by about fifty-one seconds of arc a year or one degree every seventy-two years. Since the vernal equinox is defined as the point where the Sun (ecliptic) crosses the celestial equator, this not quite getting back to the same spot each year is why there is the westward motion.

Due to precession, the vernal equinox moves inexorably westward around the whole zodiac, taking approximately twenty-six thousand years to complete a cycle. One complete ‘wobble’ of the earth on its axis creates one full rotation of the equinox points around the ecliptic plane.

The most recent point in time when the Vernal equinox did coincide with 0° Aries as marked by the fixed star Citrā was around 285 A.D. The cumulative effect of the precession of the Vernal equinox currently has resulted in a shift westward of about 24° according to the Lahiri system which is the most commonly relied on calculation. The slowly widening gap between Sidereal 0° Aries and the vernal equinox equated with 0° Aries in the Tropical system is known as the ayanāṃśa (moving portion).

While the Vernal Equinox still occurs within a few days of March 21st, the position of the Sun against the background of the stars is now at roughly 6° of Pisces. It will be another twenty-three thousand or so years before the vernal equinox occurs at 0°degrees of Aries again. Today this translates to an approximate 24° gap on the placement of the planets between Sidereal and Tropical Zodiacs as they travel the ecliptic. It is not a matter of one is right and one is wrong. They are both accountable divination systems but the Sidereal system aligns for the most part with the back drop of fixed stars against which you would observe the graha with your naked eye or through a telescope.

The Truth in the Sky

While stargazing during the late summer's evenings, Jupiter and Saturn are in full view high in the sky. At first glance, they looks like stars, but they are larger and strikingly brighter, all the more so because both are retrograde.

The Sidereal system locates Saturn in early Capricorn and Jupiter towards the end of Sagittarius. In contrast, the Tropical system places Saturn further west in the late stars of Capricorn with Jupiter mid-way through Capricorn. But what does the sky show?

Jupiter is right among the stars of Sagittarius.

Saturn is dipping its toe into the beginning of Capricorn.

Epilogue

It occurred to me while writing this article that on my first night stargazing on the upper slopes of Mauna Kea, Hawaii I had a very clear question in mind, “What is the wisdom that can be seen? Is Jupiter residing in the constellation of Leo, as it would be according to Tropical Astrology, or Cancer according to the Sidereal Zodiac?” As I stood under the blanket of emerging stars at dusk, I set my sights on gas giant Jupiter. The grahas are the first thing to appear in twilight and don’t twinkle like stars do. On its ascent to the highest point of the heavens, Jupiter gazed down amidst the faintly lit crab formation of Cancer.

It was only today that it dawned on me what a beautifully auspicious moment this was. With no prior knowledge of what would be visible that evening, I stood poised between the two brightest grahas, Venus setting in the west and Jupiter rising to the midheaven. This sight opened a path of knowledge through the lens of pratyakṣa and I realized that what is “near the eye” can lift the veil, leading to greater awareness.

About the Author Rose Zimmerman

I am the youngest of nine children, I grew up with a strong desire to understand relationships on a deeper level. I was introduced to the vedic sciences through yoga and I began my studies of Jyotiṣa in 2014 under the guidance of Alison Bodhani, and continued under the tutelage of Penny Farrow in 2016.

After beginning studies in Jyotiṣa, an interest in observations was sparked. It quickly led me to Mauna Kea, Hawaii, the epicenter for Astronomy research. I joined the stargazing program in 2015 at the Onizuka Center for International Astronomy and spent over two years immersed in ancient star lore and astronomy.

Attributions

- Pleiades, taken at Onizuka Center for International Astronomy

- ChristianReady / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Celestial_Sphere_-_Eq_w_Label_figures.png

- ChristianReady / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Celestial_Sphere_-_Earth_Stars.png

- celestial sphereSanu N / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)— https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Celestial_sphere_with_ecliptic.svg

- Nava grahasTop left — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Budha_graha.JPG

- Top middle — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shukra_graha.JPG

- Top right — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chandra_graha.JPG

- Center left — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brihaspati_graha.JPG

- Center middle — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Surya_graha.JPG

- Center right — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angraka_graha.JPG

- Bottom left — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ketu_graha.JPG

- Bottom middle — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shani_graha.JPG

- Bottom right — E. A. Rodrigues / Public domain — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rahu_graha.JPG